As mentioned in previous posts, just because I discuss something here doesn’t mean I’m advocating for it!

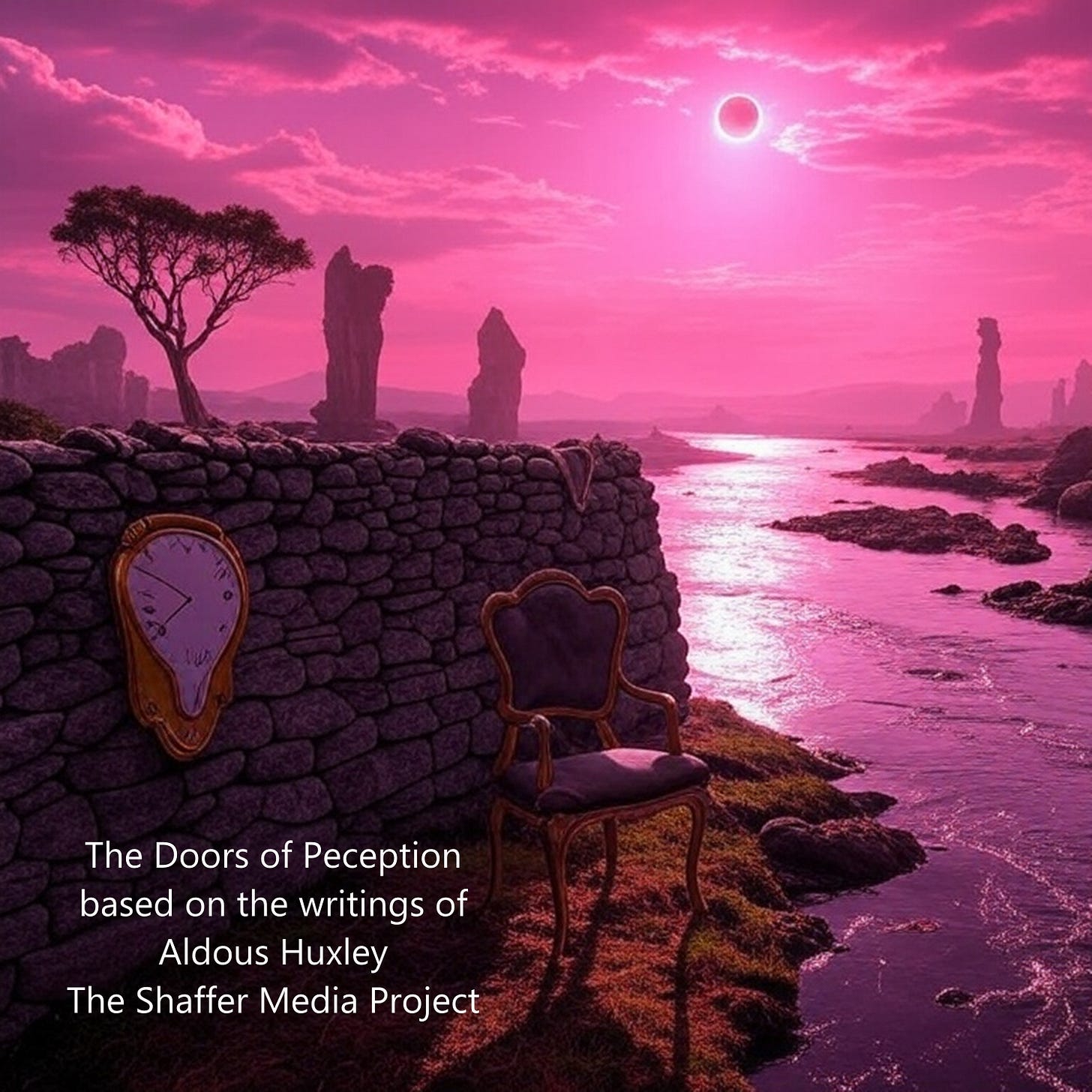

In The Doors of Perception, Aldous Huxley explores mysticism through the lens of his mescaline-induced experience, presenting it as a state of heightened awareness that transcends ordinary perception. He describes how the drug stripped away the filters of his mind, which he calls the "reducing valve," a mechanism that typically limits human consciousness to what is biologically useful for survival. Under mescaline, Huxley perceives reality in its unfiltered form, where everyday objects like a chair or a flower become imbued with profound significance, radiating a kind of sacred beauty. This direct, unmediated experience of the world aligns with mystical traditions, which often describe a state of unity and interconnectedness with all things, a perception of the "is-ness" or intrinsic being of reality that goes beyond utilitarian thought.

Huxley ties this mystical experience to historical and spiritual traditions, drawing parallels with the visions of mystics like William Blake, who famously wrote of seeing "a World in a Grain of Sand." He argues that the mescaline experience mirrors the ecstatic states described in religious mysticism, where the ego dissolves, and the individual feels at one with the universe. For Huxley, this dissolution of self is central to mysticism—it’s a shift from the isolated, analytical mind to a boundless, intuitive awareness. He references Eastern philosophies, such as Vedanta and Buddhism, which emphasize the illusory nature of the self and the ultimate unity of all existence, suggesting that psychedelics can serve as a chemical shortcut to these profound states that mystics achieve through years of meditation and discipline.

However, Huxley doesn’t romanticize this mystical state as an end in itself; he discusses its implications with a critical eye. He acknowledges that while the mescaline experience offers a glimpse into the mystical "Mind at Large"—a collective consciousness that transcends individual perception—it’s not a sustainable or practical state for everyday life. The reducing valve, while limiting, is necessary for functioning in the material world, as pure mysticism can detach one from practical responsibilities. Huxley contrasts the visionary experiences of mystics with the mundane demands of survival, noting that society often dismisses such states as madness or irrelevance, yet he argues they hold value in revealing the deeper nature of reality, offering a counterbalance to the materialist worldview dominant in Western culture.

Ultimately, Huxley’s concept of mysticism in The Doors of Perception is both a celebration of expanded consciousness and a call for integration. He advocates for a balanced approach, where the mystical insights gained from such experiences can inform art, religion, and philosophy, enriching human understanding without rejecting the necessities of daily life. By connecting his mescaline journey to the broader history of mystical thought, Huxley positions psychedelics as a tool for accessing the sacred, but he also warns of their potential for misuse, emphasizing the need for reverence and context. His work suggests that mysticism, whether achieved through drugs, meditation, or spontaneous insight, offers a vital glimpse into the infinite, challenging individuals to see beyond the ordinary and embrace a more holistic vision of existence.

.

.