The mysticism of the Quakers

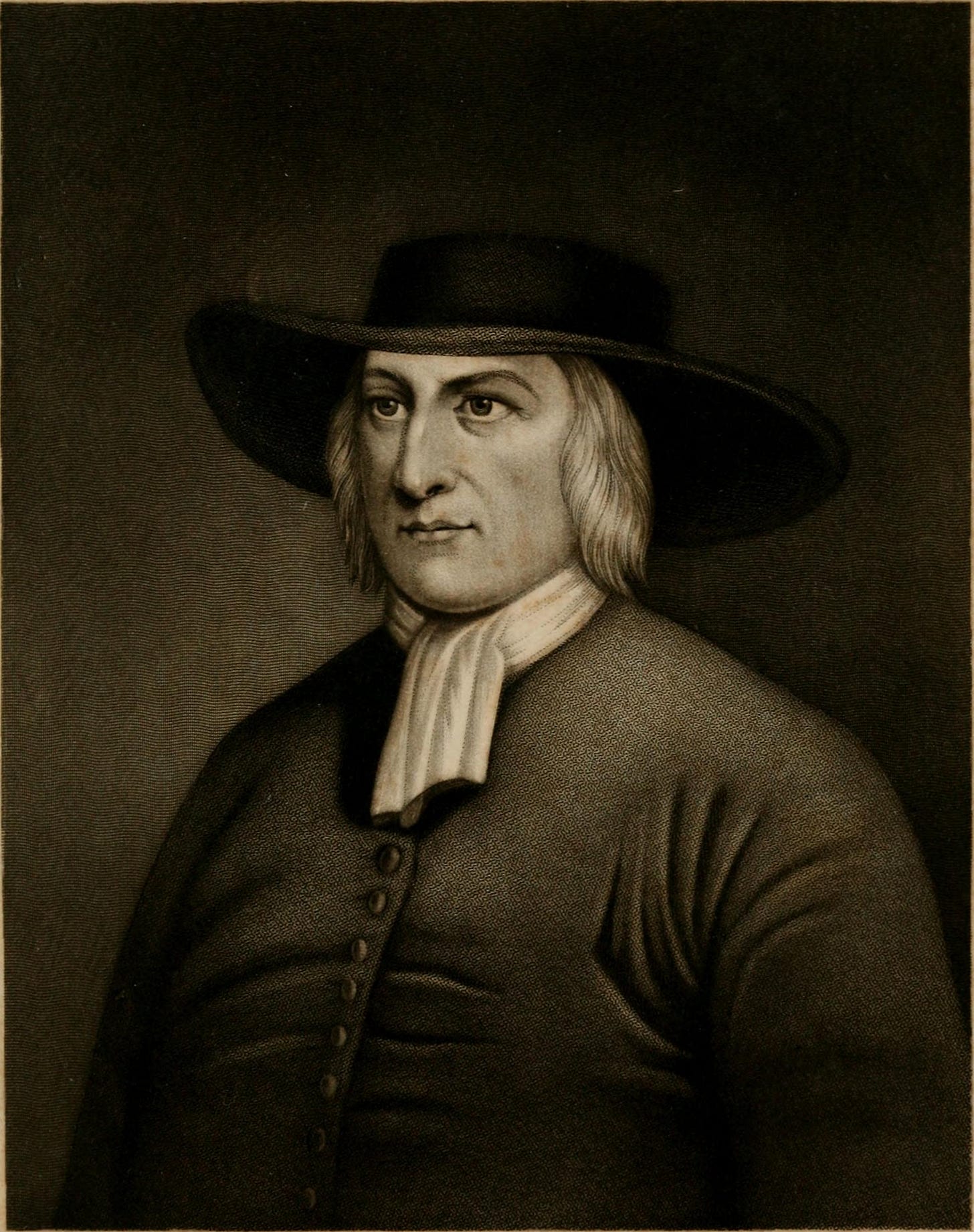

The Quaker religion, formally known as the Religious Society of Friends, emerged in mid-17th century England during a period of religious and political upheaval. Founded by George Fox, Quakerism is rooted in a profound mystical tradition that emphasizes direct, personal experience of the Divine, often referred to as the "Inner Light" or "that of God in everyone." This mystical foundation distinguishes Quakers from other Christian denominations, as it prioritizes an unmediated relationship with God over rigid doctrine or ecclesiastical authority. Fox’s spiritual journey began with a deep dissatisfaction with the established churches, which he found lacking in authentic spiritual experience. His vision of a direct encounter with the Divine, unencumbered by clergy or ritual, resonated with those seeking a more intimate and experiential faith, laying the groundwork for Quakerism’s mystical ethos.

At the heart of Quaker mysticism is the concept of the Inner Light, a belief that every individual possesses an innate divine spark that can guide them to truth and righteousness. This idea draws from earlier mystical traditions, such as those found in the writings of Christian mystics like Meister Eckhart or the Quietist movement, which emphasized inner stillness and surrender to God’s presence. For Quakers, the Inner Light is not merely a theological concept but a lived experience, accessed through silent worship where individuals gather in communal stillness to listen for divine guidance. This practice, known as "waiting upon the Lord," reflects a mystical approach that values personal revelation over external authority. It underscores the Quaker belief that God’s voice can be heard directly within the soul, fostering a sense of spiritual equality across all people, regardless of social status or education.

The mystical roots of Quakerism also manifest in its rejection of outward sacraments and formalized rituals, which Quakers view as unnecessary intermediaries between the individual and God. Unlike other Christian denominations that emphasize baptism or communion as essential rites, Quakers hold that true worship occurs inwardly, in the heart’s communion with the Divine. This perspective aligns with the mystical tradition’s focus on inner transformation over external observance, echoing the teachings of earlier mystics who prioritized spiritual purity and direct communion with God. For Quakers, everyday actions—living simply, acting justly, and seeking peace—are themselves sacred, reflecting a mystical worldview where the divine permeates all aspects of life. This integration of the sacred and mundane underscores the practical mysticism that defines Quaker spirituality.

Historically, Quaker mysticism has drawn both inspiration and critique from its radical egalitarianism and emphasis on personal revelation. The belief that every person can access divine truth directly challenged the hierarchical structures of 17th-century society and church, leading to persecution of early Quakers. Figures like Margaret Fell and James Nayler articulated this mystical vision, often at great personal cost, emphasizing that divine insight was available to all, including women and the marginalized. This democratic spirituality, rooted in mystical experience, also fueled Quaker activism, from their early opposition to slavery to their commitment to peace and social justice. The mystical conviction that God speaks to and through each individual fostered a sense of universal kinship, influencing Quaker contributions to humanitarian causes and their enduring emphasis on living in alignment with divine truth.

In contemporary Quakerism, the mystical roots remain vibrant, though expressed diversely across its liberal and evangelical branches. Liberal Quakers continue to emphasize silent worship and the Inner Light, maintaining a fluid, inclusive approach to spirituality that accommodates varied theological perspectives. Evangelical Quakers, while incorporating more structured worship, still draw on the mystical tradition through their focus on personal encounters with Christ. Across these expressions, the mystical core of Quakerism—its trust in direct divine guidance and the transformative power of inner stillness—continues to shape its identity. This enduring mysticism invites Quakers to seek God not in distant heavens or rigid doctrines but in the quiet depths of their own hearts, fostering a spirituality that is both profoundly personal and universally connected.